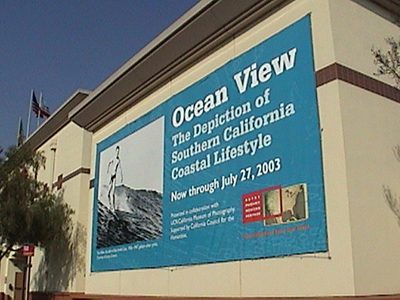

Exhibit Overview

Ocean View was a study of coastal lifestyle mythology as an extension of the greater Sunshine State mythology that was designed to draw industry, wealth and population to the state in the earlier portion of the century. The manufactured image of health and happiness that became synonymous with the California Lifestyle is refined and molded into a more specific state of existence that is by definition, placed at the ocean’s edge.

Defined initially by the citrus and travel industry, the search for eternal youth and health lead to the life played out on the beaches of California. Early developments that marketed the lands adjacent to the coast followed the paths of the red car. Expansion of the infra structure of transportation made both work and the pleasure of life on the beach possible. The foundation for the tradition of commuting was being established within a landscape that would later be identified by its relationship to both the coastline and the freeways. Interests in oil and real estate became as equal to the weather as forces of change.

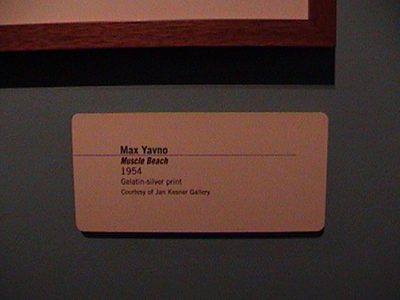

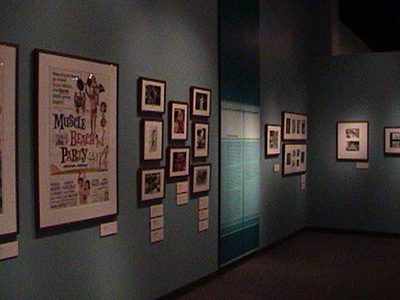

The images of California beaches in the post World War II era portray a country healed by the body conscious practices of the inhabitants of Muscle Beach or soothed by the vision of pristine landscape, and beautiful people. An extension of the circus like atmosphere of the amusement park industry, which had utilized the piers as fun zones since the turn of the century, images of Muscle Beach define the health conscious paradigm of leisure activity. This life of play was the fringe benefit for a well-employed populace that was increasing with the development of post war economy and industry. Fueled by the return of veterans who discovered California during their service in the Pacific War, the population of the state began an unprecedented period of growth. To these transplants, the California Lifestyle was as much a possibility as it was an illusion.

The beach films of the early sixties follow an outgrowth of the light entertainment films of the post blacklisting era in film when controversial or debatable social issues were avoided by filmmakers. These films, combined with the images of surfing and hot rod magazines, exploited California as a place where style and appearances overshadowed a life of substance or worry. Their films were based in philosophies of the likes of American International Picture’s Sam Arkoff who stated, We don’t make art. We make money. The general populace of the state was landlocked and living average lives typical of the period. Their lifestyles easily debunk the image of the burgeoning industry that banked on the sale of the coastal lifestyle. That view of life was not what the rest of the youth of America would pay to see. The drive-in film market became the vehicle of exploitation of an audience that wasn’t going to be watching the films anyway.

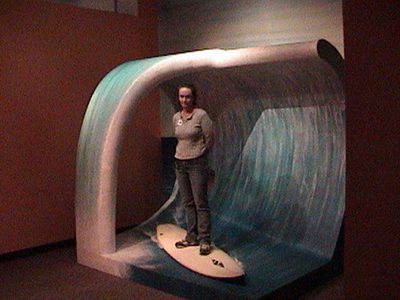

The surfing lifestyle was the epitome of a coastal consciousness that was under construction by the late nineteen fifties and became an industry in production by the early sixties. The evolution of the surfing industry as a strategic advertising entity can be traced to it’s origins in the backyards and garages of its’ creators. The relationship between the film industry and the business of surfing is documented in the use of surfing performances and ocean shot sequences that are the heart of the photographic substance of the surfing journal and the surfing films that were the promotional products of the day. Some of the photographers and filmmakers who pioneered the use of aquatic photographic technology, found employment within both industries because of their unique technological expertise.

A film entitled Endless Summer, was presented to Hollywood distribution concerns before the summer of 1964. Sure that the this film story/documentary about two southern California surfers’ round the world surf experiences would have audience acceptance limited only to beach cities, distributors balked and refused to associate themselves with the film. Undaunted, the film maker/surfer, Bruce Brown, rented a theater in the literal heart of America. Opening in Wichita, Kansas and with limited local advertising, Brown sold out every screening of the film for three weeks straight. It was a pivotal moment in the realization of the economic potential for the surfing industry as well as other product manufacturers that were investigating the profitability of this Lifestyle creation.

The success of the promotion of surfing lifestyle began to reach critical mass during the period associated with the teen film, Gidget. This light entertainment film that portrayed the growing away from the carefree life of the beach as a dramatic moment in the teen character’s development coincided with the discovery of the economic marketing potential of the entire East Coast Backyard and garage business that were surf related moved into industrial space. Land locked kids reached for the way to participate in the craze and found music, movies, fashion and the skateboard. The aesthetic of the beach was blaring coast to coast with a host of surf music bands, while scores of youth embarked on a dream ride that included surfboards, skateboards and all of the necessary fashion accessories.

The surfing populations grew to such an extent that locals began to band together to protect and claim territory from outsiders. The unspoken aspect of a separatist tendency became open and clearly visible as white middle class kids from inland cities poured onto California beaches and surf spots with their newly purchased surf wear and equipment to compete for waves that coastal populations saw as their own property. The only non-whites regularly pictured as part of this new surfing world were the Hawaiians whose lives and culture became romantic references to the exotic for the industry. The fact that localism and aggression targeted the inland invaders regardless of color, denies a clear racist intent by the perpetrators of the following generations of the My Wave Era. The fact that non-whites didn’t attend surfing beaches may relate to standards of separation and behavior that were determined before the surfing era. In either case, non-whites were not targetted in the marketing strategy of the coastal lifestyle cartel that included the hair color industry. Blonde was in.

The next revolution for the surf industry came with technological advances in the manufacture and material of surfboards. With the development of the short board came a more radicalized and aggressive surfing style. Surfing reflected a growing hostility in the crowded water as well as in the media representation of the beginning of the war in Vietnam. For the first time in more than a decade, American youths were facing a threat more serious than the problems of the youth portrayed in Beach Blanket Bingo. Many of the surfers who had followed the dream instead of the security and protection of college education and the deferred draft status that came with it, became eligible for the draft. The dream and the carefree coastal lifestyle was taking a turn with the rest of the nation.

With the advent of the Vietnam War and influx of drug culture and popular music, the west coast shook under the condensed pressure of paradoxical extremes. The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, the west coast version of a non-violent hippie/surfer Mafia, began to convert their summer earnings in the surfboard factories and surf shops into cash crop profits from marijuana. Purchased in the mountains of Mexico and sold in bulk in San Francisco to fuel the dreams of a cultural revolution, profits from marijuana, hashish and LSD subsidized winters surfing in Hawaii. Smugglers sailed on courses that followed the same shipping paths as those of the men and material that begin to pour towards Vietnam from the staging areas on the West Coast.

Bob Dylan had stated that his dislike for LSD was based in the understanding that everyone who took it began to, think they were a star. The mix of drug culture, war and the tenuous establishment of surfing as an industry began to transform the feeling of the beach. The frustrations of young surfers, tempered by the hopes of professionalism and grounded in the hostility and aggression of localism, became more evident. The seventies invasion of Southern California brought about a sky rocketing transformation in the value of coastal real estate. Bedroom communities such as Huntington Beach doubled and tripled their populations in a matter of a few years. The under educated and less conventionally intentioned members of the society of the surfing began to struggle to keep up with the changing economy. They could feel the sand slipping from beneath their perpetually bare feet.

By the beginning of the early seventies, the involvement of surfing interests or practitioners in the drug trade would be significant within the confines of surfing ghettos like the South Bay and Orange County’s Huntington Beach. Coastal lifestyle was akin to sailing and there was no better way to attempt the importation of drug shipments than by the lazy passive approach of small sailing craft at night. The surfer as wanderer had helped to pave the way in building loose networks that aided in the drug induced supply and demand of the era. Such occupations left plenty of time for surfing but the lifestyle had become the opposite of it’s innocent intent. There was little left that was healthy or happy about it. The dream had turned sour.

The romantic landscape and it’s relationship to the suggestion of the sublime or the infinite became passé’. VietnamAmerica’s dinner time news. The world was becoming smaller by the second and photographers could no longer separate themselves, or the effects of humankind, from the landscape. The subject had become inseparable from the setting. Both landscape and humankind were locked into the same informational and ecological frame. One could not be seen without revealing traces or references of the other. Smog, gridlock and the limitations of nature could not be ignored as a concern for relevance began to overshadow the image of a dream. and the war half a world away, had become part of it.

The record of the coastal lifestyle by fine art photographers of the seventies and eighties was produced with an awareness of the consequence of an imaging strategy. These photographers, based near Southern California The recognition of a new order and the limitations and implications of restriction that were synonymous with change were instantly recognized. There was no longer a search for the romantic moment or a grand vision that separated the choice of humankind from the landscape. Instead, a steady vigilance was practiced with an attentiveness that was focused on the nuance and meaning of the everyday transition of detail.(mise en scene’ ) beach cities, were witnesses to the history and development of socioeconomic trends and the gentrification of beach property. Their view of the beach, as a subject or place, was not as naive.

Reacting more from the influence of work like Ed Ruscha’s views of Every Building on Sunset Blvd. than to Ansel Adams, these photographers began to ignore the traditional views of the ocean because of the romantic and tradition laden nature of the subject. The information and change that initiated this response was not specific to the beach only, but was the beginning of a new way of seeing. The search for an iconic paradigm of nature had been traded away for a serial approach to viewing the subtle change of the everyday. Evidence was being collected.

Images and information became as one. The implications of environmental study and ecology began to influence a more elemental approach to understanding. This formal reduction to seeing, recording or studying human activity provided a distanced approach to image making that was, at the same time, more revealing of human nature. That is a view of nature that includes human activity as a part of the nature, no matter how urbane the construct may seem. Sections of wilderness were understood as that which had been selected to remain in a natural state. The process of selection was still a choice that was exercised by man. A group of photographers were christened as practitioners of New Topographics. Their photographs included the process and the effects of incursion on the landscape. Much of their work was focused on the process and change brought about by real estate development of Southern California and it’s coast.

Extensions of that view have been found in current photographs, which function as portraits within the landscape. These works record the harmony or, disharmony , which exists between the subject and their surroundings. Utilized as an element which made the landscape of the early American wilderness seem less daunting, the figure now occupies the portrait as an indicator of sociological and anthropological importance. They are too like a kind of evidence, a story, or a dream being lived. They might seem like a reflection of a more urbanized and technologically aware populace, a populace sensitive to the fragile balance of nature that exists at the edge of that narrowing strip of land referred to as the beach. They are us, on a day at the beach.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Receive news about collections, exhibitions, events, and more.