Exhibit Overview

Almost all of the seventy-eight artworks selected for the exhibition were created between 1990 and the present. This period coincides with a particular development in the contemporary art world in the 1990s as artists and critics responded to the emergence of intellectual movements such as poststructuralism, postcolonialism, and multiculturalism, from which arose the cultural study of whiteness.

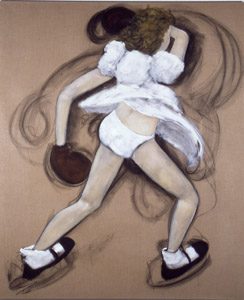

Generally, these schools of thought profess profound skepticism toward many concepts and values that have been central to Western culture. These include the individual, reason, truth, freedom, institutions, the nation, history, and almost any approach that attempts to fit the nuances of diverse events into an overarching narrative that suggests they followed a natural progression. Because of its concern with power structures and the ideologies behind them, postmodern theory was of particular interest to artists whose work was informed by the social activist movements that emerged during the 1960s and 1970s, such as civil rights, feminism, and gay activism.

The ultimate goal of the cultural study of whiteness is simply to recognize the United States as a multicultural nation, where in a census whites should be viewed as just another Other. Despite this goal, however, the background will always be the effects of whiteness as the dominant culture, one that cannot be easily dismissed, even if being white becomes a category with its own history. This exhibition attempts to put its faith in the complex ambiguities of art, which works against the development of stereotypes and where uncertainty is life affirming.

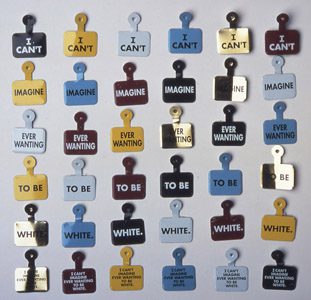

The artworks in this section explored how whiteness develops into an unacknowledged yet dominant value system. It explored topics such as the association of the color white with purity, Manifest Destiny as justification for geographical expansion, present-day consumerism as a continuation of this destiny, and Western attitudes toward the art of non-Western cultures, often defining those cultures as primitive.

The symbolic associations of white and black, for example, have been firmly fixed for thousands of years. In texts such as the Bible, black is the color of affliction and calamity: I go about blackened, but not by the sun; I stand up in the assembly, and cry for help. (Job 30:28). White, by contrast, is associated with holiness and purity: Many shall purify themselves, and make themselves white, and be refined; . . . (Daniel 12:10).

Previous museum exhibitions that have dealt with identity have, for the most part, presented only images of non-whites and not those of whites. This is perhaps due to the relative abundance of works in which artists reread and reinterpret dominant culture and define themselves in relationship to it. The artists in the White Out section of this exhibition explored the invisibility of whiteness, how it is depicted as generic and the norm. Their works pointed to the subtle internalization of ideas and how an individual can begin to act, albeit unconsciously, in accordance with what is considered to be normal.

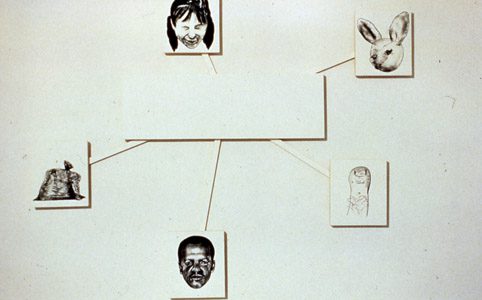

The artists in the Mirror, Mirror . . . section of this exhibition, like those in the first section, White Out, looked at how whiteness operates, but they hold up a mirror, forcing those identified with white culture to look at images of themselves.

Most of the books on the cultural study of whiteness have been published only since 1993. There are several earlier authors who considered whiteness—most notably W. E. B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, and Ralph Ellison—but there has never been such a plethora of academic writing on the subject, especially by those defined as white.

Nineteen ninety-three was also an important year in the contemporary art world because of that year’s Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The Whitney Museum’s director at the time, David Ross, shifted the focus of the two-year survey so that—rather than taking the temperature of a pluralistic art market, as previous biennials had done—the exhibition charted a particular phenomenon. That phenomenon was the degree to which artists working in the United States, largely ones not represented in the commercial gallery system, were exploring the construction of identity. Ross’s change in the Biennial can also be viewed as a response to exhibitions in the 1980s that began to look at the visual arts in non-Western cultures, such as the 1984 exhibition Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern at New York’s Museum of Modern Art; and the 1989 exhibition Magiciens de la terre, held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

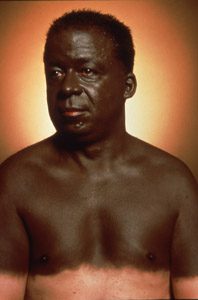

During the 1990s other museums around the country were also exploring expressions of identity in contemporary art. Exhibitions that recognized this development among artists included: The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s (1990), co-organized by the New Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, both in New York; La Frontera/The Border: Art about the Mexico/United States Border Experience (1993), co-organized by Centro Cultural de la Raza and the Museum of Contemporary Art, both in San Diego; Partial Recall: Photographs of Native North Americans, The Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism (1993) at the art gallery of the University of California, Irvine; Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art (1995) at the Whitney Museum of American Art; In a Different Light: Visual Culture, Sexual Identity, Queer Practice (1995) at the University of California, Berkeley, Art Museum; and Too Jewish? Challenging Traditional Identities (1997) at the Jewish Museum in New York. (1993) at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia.

As is evident from the number of these exhibitions and their titles, this was a period in which naming was important. Naming is about finding a new set of words to define one’s identity as a method towards self-determination, but the very need to locate an identity also points to the mechanism of domination that either prevents the naming or imposes a different name.

The application of the word white to an individual in the United States has a history that is more about regulating marriage, property rights, citizenship, and voting, with people of differing skin color having been placed within the category of white. In the first census in 1790, government officials defined four categories: free white males, free white females, slaves, and others. Today, there are two distinct questions. The first concerns Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino heritage with sub-categories of Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or other Spanish/Hispanic/Latino group. The second question concerns so-called race, and there are fifteen categories: White; Black/African American, or Negro; American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian Indian; Japanese; Chinese; Korean; Filipino; Vietnamese; or Other Asian; Native Hawaiian; Guamanian or Chamorro; Samoan; or Other Pacific Islander; or Some other race. However, the attributes of these categories are not parallel and bear a complex history, as some are about color, while others are about geography or culture, and some a mixture of both.

People, who answered the first question as being Latino, would then answer the second question as white, often equating white with wealth and power. A recent newspaper article in the Los Angeles Times reported that Latinos living in affluent, suburban parts of Los Angeles tended to identify themselves as white in Census 2000. By contrast, 50% or more of Latinos living in the urban barrios of Los Angeles selected some other race for their racial identity. The multiple choices offered by the 2000 census are an acknowledgment of how complex the selection of identity has become. In the United States today, the choice is less about biology—the one drop rule—and more about cultural affiliation and economic status.

The majority of the artists in the exhibition work in California. This regional focus is fitting because the state has crossed the threshold into a white-minority society. California is home to 10 percent of the nation’s population, so the state may be a bellwether for the rest of the country. The selection of artists is not restricted to whites, as defined by the census categories, but includes artists of various ethnicities.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Receive news about collections, exhibitions, events, and more.